The Amana Colonies

Iowa

1962

I was a junior in high school the year my mother and I stopped for lunch at the Ox Yoke Inn, a restaurant in a village in the Amana Colonies. She was driving me back home from the University of Iowa in Iowa City following a journalism workshop for incoming high school newspaper editors, like me, from around the state. I was a quiet introvert feeling more independent after my week on a college campus. I ordered lunch with a bit of aplomb, choosing among schnitzels, sauerbraten, rhubarb custard pie, the old-world German favorites.

“I see a difference in you,” my mother said. “You’ve changed this week.”

She looked away and turned her head slowly side to side.

“I worry what people will think,” she said. “People don’t like anyone getting above their place.” She often talked about what people thought—about her, about me, about running a store in a small town I had dubbed, aptly, Isolate.

I did not rise to my mother’s comments. Instead, my thoughts drifted to the photo of knitters on the back of the menu—or was it on a wall near our table? In the photo, circa 1890, an older woman was teaching a young girl to knit. Both wore long calico dresses and traditional Amana caps, black and snug fitting. They tended to their knitting, a moment of closeness.

I understood the feeling.

Years earlier, my Danish grandmother had taught me garter stitch knitting. My seven-year-old self had put aside yarn and needles after I failed to knit a perfect dishcloth. At fourteen, I had picked up knitting needles and yarn again, thrown open the window to learning about the knitting world, and never looked back.

Finding knitters in Amana was exciting.

I read further about the Amana Colonies. Nineteenth-century German immigrants—the Community of True Inspiration—had settled this verdant, rolling farmland and established seven villages along the Iowa River. A communal society in the early days, the people of Amana built churches, calico and woolen mills, communal homes, laundries, and kitchens. Communalism ended in the Thirties, but the heritage had continued. Tourism flourished.

My eyes fell eagerly on a photo of hand-knitted mittens. Curious, I studied the cunning arrangement of tiny geometric crosses on palms and thumbs. What amazing thumb gussets! How had the knitter kept the patterns so even? This was regimental knitting. And what fun to knit snowflakes and reindeer on the mitten backs!

Ribbed cuffs had simple stripes. Well, quite a relief after the other disciplined knitting with all that mathematical color shifting from sienna brown and white or indigo blue and white. Wool, of course, warm and cozy, perfect for harsh Iowa winters. I was intrigued. The mittens looked like magazine photos of Norwegian knitting. Were these mittens a traditional part of history in the Amana Colonies? How would the patterns have moved from Norway to Germany to Amana?

“I mean, we run a business in town,” my mother said. Startled, my thoughts jerked away from knitting in Amana. “Be careful you don’t act like you think you’re better than anyone else because you got to go on that course,” she said. “It could be bad for business.”

Would a course in editing and writing—something I liked a lot—put me in danger of getting above my place? I felt a smidgeon of pride that my writing ambitions might violate the Midwest ethos for girls at the time. Acceptable careers for girls were teacher, nurse, typist, office worker, that kind of thing. Or farmer’s wife, possibly with a job at the county courthouse. Bonus points for teaching Sunday school.

When I was eleven, my life had taken a deep dive for the worse after my parents moved to Isolate, Iowa. Population 1,200 or so souls. Isolate was flat. I could stand on a curb at the edge of town and see for miles. A neon sign on the Majestic Theater—movies Wednesday and Saturdays—was the sole distinguishing architectural feature along two blocks of Main Street. A grid of gravel roads surrounded Isolate, bounded by fields of corn and more corn. Isolate was White, Protestant, Midwestern, Straight. Growing up, I heard smug comments and jokes riddled with racism, antisemitism, and homophobia. It was disturbing.

Earlier in the year, Mr. Curry, the high school guidance counselor—he also taught biology and coached basketball—had met with each high school junior about career plans. “I’m interested in anatomy and medicine,” I told him. “I think I want to be a doctor, maybe a psychiatrist.” I did not tell him that, on the sly, I read my psychiatrist uncle’s gross anatomy and abnormal psychology textbooks secreted away on a dusty bookshelf in our basement.

Silence.

“Mr. Schroeder tells me you’re one of the best typing students he’s ever had,” said the counselor. My typing teacher was also the high school principal.

Silence.

In Mr. Curry’s biology class, I had illustrated my paper on the anatomy of hearing with painstaking watercolors of the incus, stapes, and malleus, the exquisite and fascinating bones of the middle ear. During class, I handed in my paper from the back row to the front of the classroom, my illustrations on the cover.

"Did we need to put that artistic crap in our paper?” smirked a boy in the front row.

“No,” said Mr. Curry with a nearly audible roll of his eyes. I stared at the floor, embarrassed and ashamed. Later, he returned my paper with the stinging comment, “Grade A. Drawings for this paper were not necessary.”

I would earn my first master’s degree in biomedical illustration.

Classmates teased me about my grades. “Guess who got an A again?” “So you must be one of those who scored 99+.” The Iowa Test of Basic Skills was not a measure of intelligence so much as proficiency with language, my strength. And I had no dyslexia, dyspraxia, dysgraphia, or other such roadblocks to learning. I read, wrote, memorized whatever I needed to memorize to pass tests. I was a good student and knew education was my way out of Isolate.

My education in Isolate had been tough going from the start. Sixth-grade teacher Mrs. Rogers, gray-haired and imposing, could deflate fragile egos with a single jab. Sit down. Be quiet. No one cares what you think. Whoosch! Seventh-grade students taunted novice teacher, Miss Murray, into a sobbing heap. One seventh grader, vile and disruptive, was banished to a desk locked inside a basement supply room. I felt only relief. A classmate disappeared mid-semester, whispered to be pregnant, married at fourteen to her high school senior boyfriend, her education over. I never saw her again.

Eighth-grade teacher Mrs. Olson tolerated no challenges. Vitamin D did not travel through windows, she lectured one afternoon, you had to be outdoors to get your Vitamin D.

“Why is that?” asked the boy seated in the desk beside me. He raised his hand, confident and curious. “Does vitamin D collect on the glass? I mean, could I scrape off a layer of vitamin D from the outside of the window?” I was all in to learn more. Mrs. Olsen’s mouth drooped into a scowl.

“Doesn’t matter,” she snapped. “We’re not here to listen to your questions.”

“Oh,” he said. His head drew back as though struck. I shrank lower in my desk, embarrassed for him. Next semester, that boy’s parents transferred him to a boarding school. He would graduate from Harvard and go onto a remarkable career in science.

In Isolate, I learned to keep quiet.

Back then, four years of basic high school education—math, science, English, social studies—in Iowa was a good foundation. Otherwise . . . no electives except typing.

Home Economics? I could already sew my own clothes. Woodshop? Boys only. History? Mr. Larson—he also coached football—mostly diagrammed historic battlefields eerily similar to football chalk talks. Social studies? We discussed, listlessly, weekly newsletters about current events.

Music? Choral and glee clubs rejected me, my voice too soft. Band? Rejected as having “no gumption” when I refused to play trombone, an instrument I despised. Orchestra? No, would an orchestra march at Friday Night Lights football? Second language? Why would you need to speak anything but English?

Athletics? Boys had basketball, wrestling, baseball, football, and track teams and coaches. Girls had nothing. Not until the Title IX of the Education Amendments of 1972 did federal laws protect against discrimination in education based on gender. Extracurriculars? Boys had FFA (Future Farmers of America). Girls had FHA (Future Homemakers of America). I suspected neither played a role in my future.

Given a wilder or braver disposition, I could have become a troublemaker, maybe a runaway or another pregnant dropout. A couple of us misfits did resign ourselves to roles as nerdy loners. I was never attracted, however, to the Dark Side, to teenage wildness and drinking, the aimless cruising and carnage on back country roads, sneaking off to find the bad boys at the downtown cafe.

Instead, I took up knitting.

Knitting was an introverted form of rebellion that ignited all my senses. It began when I was fourteen and bought the Learn How Book . . Basic Steps for Beginners and a skein of Red Heart knitting wool at the local five-and-dime store. Learn How Book promised to teach me all I needed to know to crochet, embroider, tat, and knit. At home, I closed myself in my room and opened the pages to “Knitting.” First, I picked up the slippery aluminum knitting needles, pulled a strand of yarn from the skein, and stared hard at the illustrations.

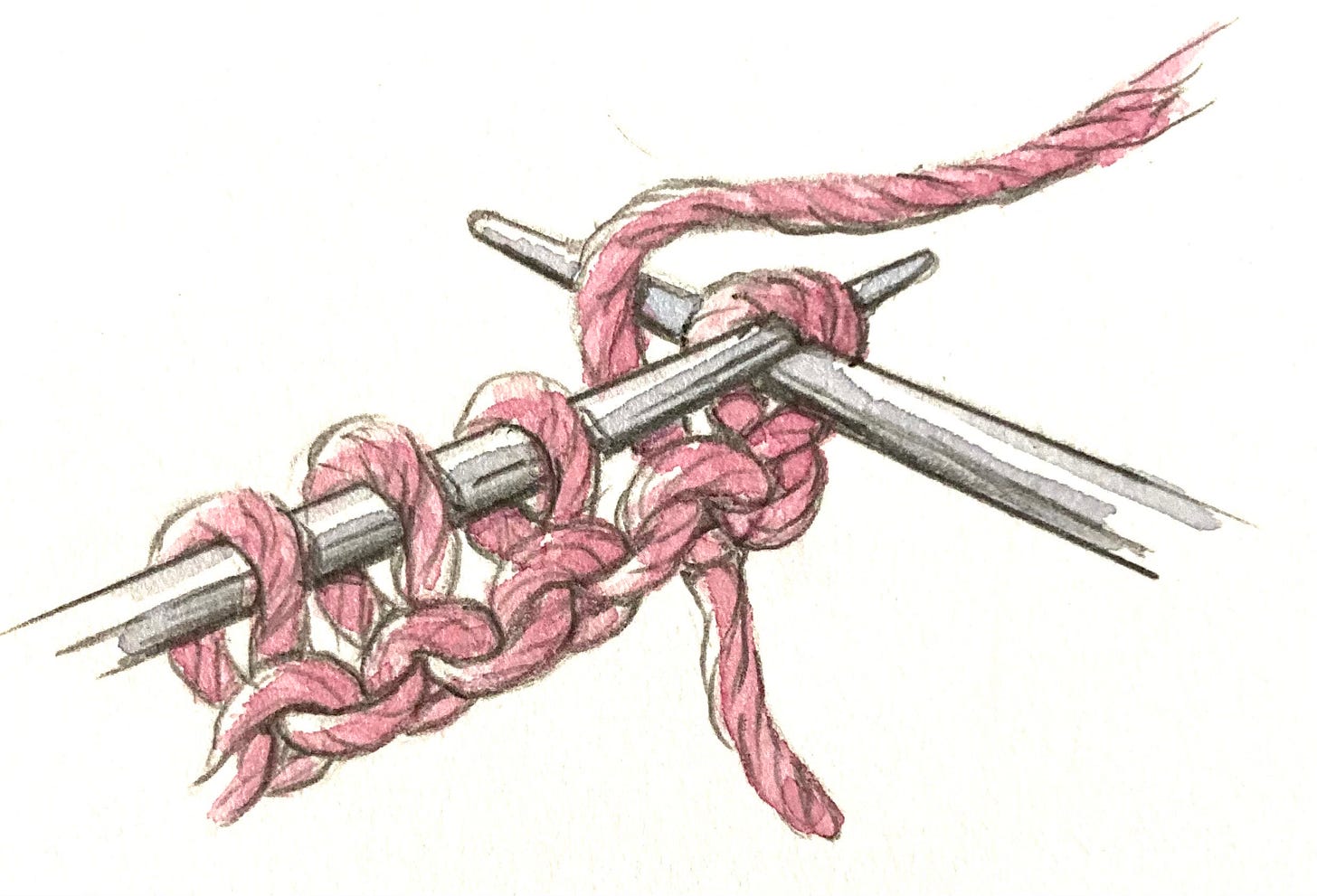

How to make a slip knot. Not difficult. Cast on. Hmm. I arranged my fingers and a strand of yarn into configurations shown in the drawings. Now and then, a knitting needle slipped from my hands and clattered to the floor. Slowly, slowly, muscle memory kicked in, and four hours later, I had cast on, knit, purl, increased, decreased, made a yarn over, knit two together, and bound off a few stitches. I glanced at the clock radio on my desk. Had four hours gone by since I opened my Learn How Book?

This was exciting stuff!

“Look what I can do!” I wanted to shout to someone, anyone. “I can make clothes with two sticks and a string!” But my parents were working at their store, I had no siblings, and I knew no knitters in Isolate. Not until my next summer stay with grandparents would a knitting mentor find me and bring me into the fold.

So I celebrated on my own by learning to read the language of knitting. I memorized abbreviations, studied the structured steps of patterns and the clever ways knitted pieces fit together to make something to wear. In Learn How Book, I scribbled my thoughts about knitting—deep thoughts, no doubt—in the margins, and I folded down corners of pages that showed the trickiest techniques.

I felt something new. Was it optimism? Every loop, every soft and fuzzy stitch, was rewarding. Knitting engaged and, at the same time, quieted my mind. Knitting had taken me to a better place. Disappointment in Isolate made me sad. Knitting made me happy.

Knitting opened a world of knitters and knitting somewhere out there beyond Isolate. That was comforting. I had little control over my life—home or school, teachers or classmates, beliefs held by people around me—but I was in control of my knitting. Knitting made me feel safe. Maybe it was the sharp pointy sticks I held between the rest of the world and me.

After our lunch at the Ox Yoke Inn, my mother and I did not take time to explore the Amana villages or search for a craft shop that sold mittens with reindeer or snowflakes. Ahead of us lay hours of driving, a tedious slog over a network of two-lane roads among the corn fields. I went on to a remarkably mediocre stint as editor of Tiger Tales, the weekly column of high school news in the Isolate Times.

The story of Amana knitted mittens would be there, waiting for me to find years later.

This is a beautiful piece of writing about your journey... where you had to be your own cheer-leader. Geesh! I love your illustrations... and as I've said before, your posts reach in and tug on my love of all things fiber. xoxo

I enjoy your writing and can relate to your joy in learning to knit.